To everything, there is a season…

Have you ever wondered how ice-over happens in your lake, or what is going on beneath the ice in the winter? It may seem like your lake or pond is taking a long winter’s nap beneath a blanket of frozen ice, but it is very much awake all winter long!

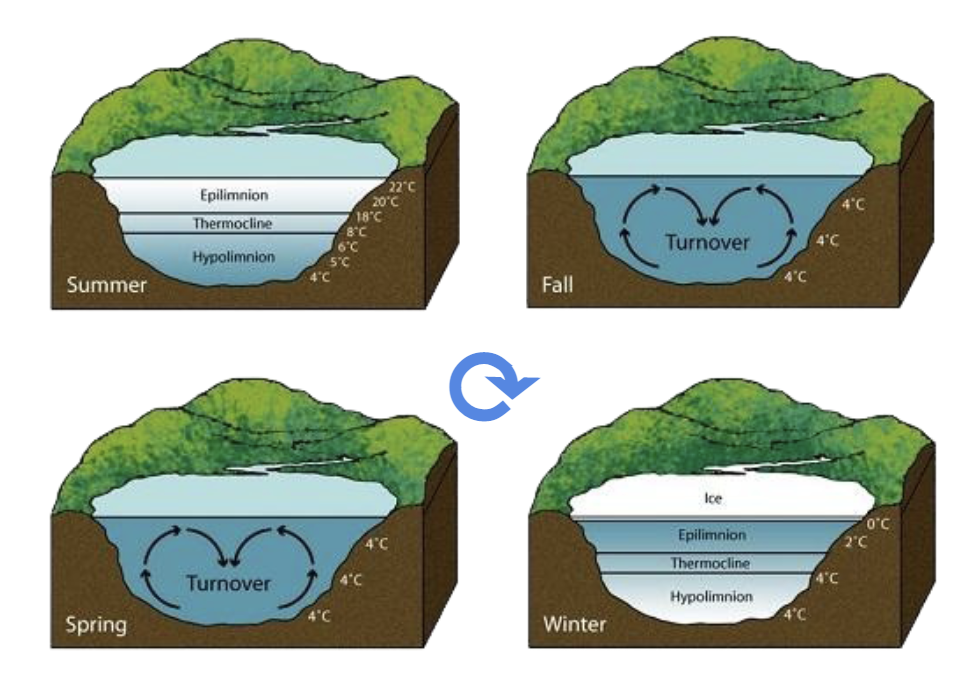

To understand how seasonal ice-in and ice-out occurs, we must first talk about lake turnover – a phenomenon in which the entire water column of the lake mixes together, and both the water temperature and oxygen levels are consistent from the surface to the bottom. Lake turnover typically occurs twice per year in most lakes – once in the fall, and again in the spring. Turnover is critical for lake ecosystems because it replenishes and redistributes oxygen and nutrients throughout the water column.

Source: National Geographic Society

In the summer, most lakes are thermally stratified with the warmest (less dense) water at the surface, and the coldest (most dense) water at the lake bottom at a temperature of 4°C or 39.2°F. This is a unique characteristic of water:It is most dense at 4°C, and less dense when it becomes colder or warmer than 4°C. As air temperatures get colder in the fall, the surface of the lake cools and eventually reaches the temperature at which water is most dense (4°C). The water at the lake surface then sinks to the bottom and pushes the relatively warmer water below it up to the surface – mixing or turning over the lake until the entire water column reaches 4°C. As fall turns into winter, temperatures at the lake surface will cool the water below 4°C, at which point it becomes less dense, and freezes into ice.

So what’s going on under the ice?

Life under the ice adapts to the colder and darker conditions. Cold temperatures result in lower metabolisms, and most fish, especially warm and cool water species, spend most of their time near the bottom where food and the warmest water can be found. Coldwater fish, like trout and salmon, will stay more active throughout the water column all winter long – cruising the colder waters just below the ice where oxygen levels are highest. Frogs, turtles and other amphibians hunker down and enter a state of hibernation within the mud and sediments at the lake bottom.

Life slows down, but certainly does not stop for smaller organisms like phytoplankton (algae) and zooplankton (microscopic invertebrates that feed on algae). While some species enter into a resting stage and settle to the bottom where they overwinter, recent studies have revealed that several species of phytoplankton and zooplankton remain active just below the ice – supporting the lake food web all winter long.

To learn more about winter lake limnology, watch the recording of Lakes Environmental Association’s (LEA) Research Director, Ben Peierls’, talk on ‘Winter Lake Monitoring: Life and Limnology Under the Ice’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tNGxTTjlvA0

Here Comes the Sun

In spring, the sun becomes stronger, air temperatures rise, and ice-out begins. As the ice melts, the water slowly warms from freezing (0°C or 32°F), eventually reaching 4°C (most dense!). The surface water will then sink down in the water column, triggering spring turnover, and the process begins again.